Ever Wondered What the Catholic Bible Is Called?

Let’s be honest: at some point, whether it’s during a trivia night, a dinner party, or that one family reunion where your uncle insists he’s found a new conspiracy about Bible translations, you’ve probably heard someone ask, “What is the catholic bible called?” And you, noble seeker of wisdom (or just someone with decent Wi-Fi), are here for an answer. Good news! You’re about to plunge into the surprisingly eventful history behind the Catholic Bible and its (many) names.

How Many Books Does This Bible Have, Anyway?

First, let’s get one thing straight. If you thought the difference between Catholic and Protestant Bibles was just a matter of dust jackets or font choices, surprise! It’s all about the count. The Catholic Bible boasts 73 books, while the Protestant Bible sticks to 66. That’s right: Catholics get seven bonus books, plus a smattering of special additions tucked into classic titles like Daniel and Esther.

Of course, these “bonus books” aren’t for padding your bookshelf. They’re called the deuterocanon (which definitely sounds like a Star Wars planet, but isn’t). For the record, the Protestant crowd refers to these as “the Apocrypha.” The distinction? Catholics say these books were received into the canon later – not less authoritatively, just later. Protestant Bibles align to the slimmer Hebrew canon, Catholics stick with the broader list, including Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, 1–2 Maccabees, and those aforementioned extras in Daniel and Esther. Catholics: the completists of Christianity.

The Catholic Bible—A Name Game With Saintly Consequences

You asked for the name, so here we go. Drumroll, please!

In official lingo, it’s typically called… wait for it… the Catholic Bible. (Catholics: masters of practicality.) But, as with all things religious, that’s just the opening act. When it comes to English translations, the Catholic Church’s most storied edition is the Douay–Rheims Bible. Yes, it rolls off the tongue like a vintage wine and sounds a teensy bit like you’re also reviewing the latest in French cheese boards. But this isn’t just any translation; it’s been the backbone of Catholic scriptural life, especially among English speakers, since the late 16th century.

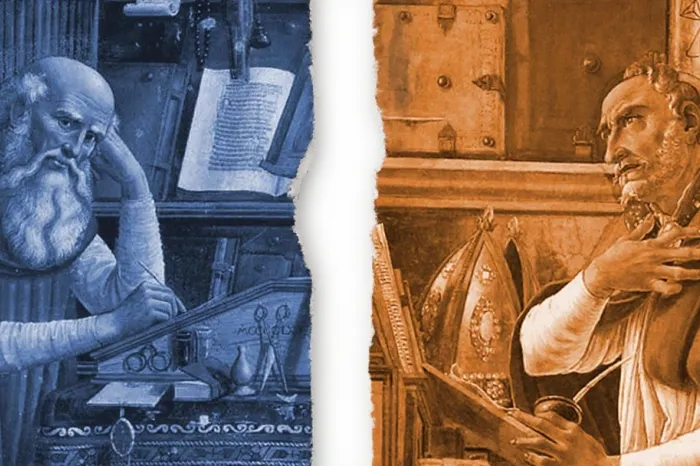

The Douay–Rheims, first cooked up by scholars from the English College at Douai and Rheims as a comeback to the Protestant Reformation, translated directly from the Latin Vulgate. It hit shelves (or, let’s be honest, candlelit desks) in two parts: the New Testament in 1582, then the Old Testament in 1609–1610. For those who prefer their Bibles with revisionist flair, Bishop Richard Challoner revamped it in the 18th century—smoothing out the Latinisms and sentences that tangled readers like a bowl of ecclesiastical spaghetti.

Manuscript Mayhem: The Vulgate Connection and Beyond

So, why all the love for the Douay–Rheims Bible? Its roots go deep. The Latin Vulgate, translated by St. Jerome just as the Roman Empire was figuring out how to survive without togas, served as the source. The Douay–Rheims stuck close to Jerome’s text, dazzling with formal equivalence—meaning it tried to stick as closely as possible to the original wording, whether it made sense or not (Bible readers: amateur cryptographers since 1609).

But if you walk into a Catholic church today, you’re just as likely to find parishioners using the Jerusalem Bible, the New American Bible, or the Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition. The Douay–Rheims endures as the darling of traditionalists and internet polemicists everywhere, while the other versions get top billing on the church’s lectionary circuit.

Wait, Didn’t Catholics Just Make Up Their Own List?

Let’s address your uncle’s conspiracy theory for a moment. Some say Catholics just padded their Bible during the Council of Trent in 1546, but the real backstory is more tangled than your headphones after three seconds in your pocket. Early Christians, keen on reading whatever would get them closer to holiness (or just keep them awake during long Roman winters), didn’t have a finalized list. There were canonical lists, deuterocanonical lists, books for piety, and books for doctrine. Debates raged—with Jerome arguing for a leaner canon and Augustine shrugging, “But if people are reading it, why not?” (Note: Not an actual quote, but historian-approved paraphrase.)

By the Council of Trent, Catholics drew a line in the ancient-sand and declared their list official. The seven books, plus assorted additions, got a full upgrade to canonical status. Protestants, meanwhile, stuck with the tradition that matched the Hebrew texts. Cue centuries of debate that would make even the most patient theologian consider a career in sourdough breadmaking.

Fun Facts For the Next Time You Want To Impress Your Friends

- The Douay–Rheims was once illegal to own in Britain. You weren’t just buying a Bible; you were basically getting a ticket to a secret club for religious rebels.

- The books called Ezra and Nehemiah in most Bibles are called 1 and 2 Esdras in Douay–Rheims. And “Paralipomenon?” That’s just Chronicles with an epic Greek name.

- Bishop Challoner’s revisions borrowed so heavily from the King James Version, some Douay–Rheims editions sound suspiciously familiar… just with extra books in the footnotes!

- The Psalms’ numbering system could spark a heated family argument. Douay–Rheims follows the Vulgate numbering, which does NOT match the Protestant versions. Double-check before you bust out that Facebook meme.

Why Does It Matter? Aren’t All Bibles Sacred?

Of course, all Bible versions carry spiritual weight. But for Catholics, canon means authority—the resounding yes to “is this teaching reliable?” The different lists have real-world doctrinal consequences. Indulgences, purgatory, prayers for the dead—these are all shaped by those extra books in the Catholic Bible. So when someone asks, “What is the catholic bible called?” they’re really opening a centuries-long debate about what counts—and who gets to decide.

The Takeaway: Names, Numbers, and Never-Ending Nomenclature

To sum it up, the Catholic Bible is, well, called the Catholic Bible. In English, its most historic translation is the Douay–Rheims Bible—though modern translations like the New American Bible and the Jerusalem Bible might be more widely used in your local parish today. Catholics accept 73 books, Protestants 66, and the difference boils down to both theological hair-splitting and the drama of centuries past. Want to cause a stir at dinner? Mention “deuterocanonical” and watch the conversation turn biblical.

So, next time you’re confronted with that question, you’ve got an answer fit for a scholar—or a stand-up comedian. Just remember: whatever version you find, it’s sure to contain drama, history, and enough footnotes to keep both saints and sinners on their toes.